SET

OTT

2021

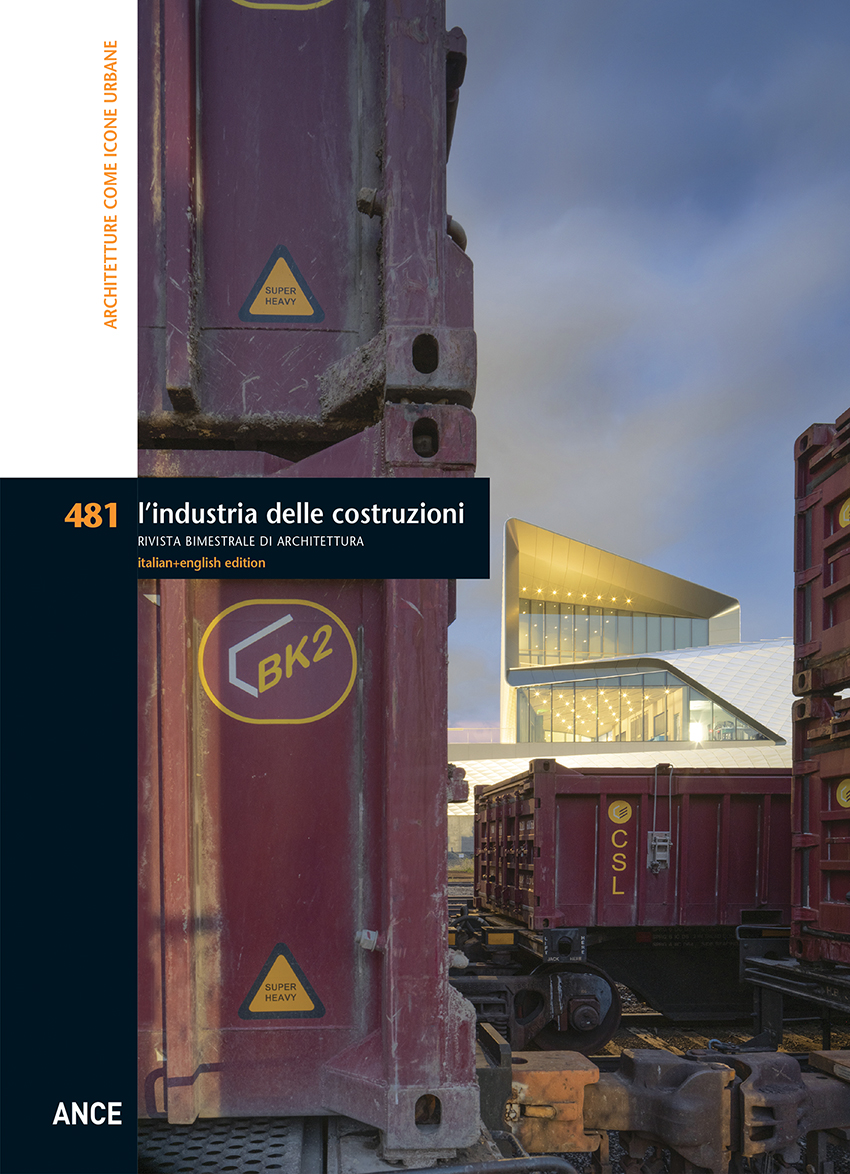

Architectures as urban icons

“In the context of widening political divides and growing economic inequalities, we call on architects to imagine spaces in which we can generously live together”. With this effective assertion, Hashim Sarkis, curator of the 2021 Biennale, summarizes the objectives of the 17th International Architecture Exhibition, currently ongoing in Venice. It is no coincidence that these questions come to light during the pandemic crisis, that has awakened urgent attention towards the global environmental emergency and the priorities established by the UN 2030 Agenda, at the centre of which is the theme of sustainable development and measures to combat climate change, desertification, poverty and to favour the socalled ecological transition. Therefore only a global change in lifestyles can mark a change and we need to call upon architects to contribute to new visions of the world. From these reflections, we started looking curiously at what architects were doing, with the idea of identifying the orientations and approaches of some of the most well-known contemporary designers in their latest creations. A selection of highly iconic buildings has emerged, in which the aesthetic composition is based on the pursuit of uniqueness and originality. These architectures rely on their capacity to direct attention to the designer’s authorship and originality, to the prestige of the client or to the attractiveness of the urban context to which they belong and are marked by a sophisticated self-referentiality. The opportunity to leave a mark in the most disparate places on the planet seems to prevail over the commitment in dealing with today’s complex social and environmental problems. The works of great architects have always played an important role in enhancing power relations within societies and the same happens today, with iconic architecture at the service of the capitalistic globalization. As argued in Leslie Sklair’s essay, the difference is that while until the mid-1950s architecture was mainly linked to the interests of state and/or religious power, contemporary architecture tends to express the demands of those who owns and controls large transnational scale corporations. Architectural products, with their exhibited formalisms, contribute in an incisive way to convey the client’s demands. Exemplary in this sense are the department store in South Korea by OMA, the LUMA Cultural Centre in Arles by Frank Gehry and the Atelier Audemars Piguet Museum in Switzerland by BIG. The distinctive features of these buildings are strongly linked to the promotional message required by the respective lenders. OMA’s building, a monolith with a sculptural appeal that suddenly emerges in the fabric of the “generic city”, plays on the theme of displacement through material effects, hybridizing the classic typology of a commercial hub with the presence of a public promenade that breaks free of the volume and protrudes on the façade in the form of a faceted geometric glazed tunnel. Also Gehry relies to the sculptural behaviour as the only way to bring out its tower in Arles. The swiss heiress Maja Hoffmann imagined the “architect of free forms” as the ideal designer of the master plan and principal building of this cultural hub in France. A more subtle operation, based on similar principles, is that carried out by BIG in the building commissioned by the famous watchmaker Audemars Piguet, to exhibit its products and renew the image of the company. In this case the context, which is the typical swiss alpine environment, offers the opportunity to design an almost perfect icon: the building, with its double spiral movement, evokes the mechanics of clocks and, thanks to the green roof, integrates perfectly into the surrounding landscape. Observing the above mentioned works, together with the others presented in this issue, one aspect emerges clearly: architecture holds today an high and effective communicative power; it is an integral fragment of the media system and takes part in it with singular exploits that often carry the aesthetic dimension well beyond the simplest correspondence between form, function, structure, context. Going back to the initial issue, several questions arise: can the architectural project still be supported by a social and political vision or it is a mere response to the needs and requests of a client? The architect is still able to play an intellectual role? Is he still capable, through the construction of space, to anticipate the society of the future? The modern idea of architecture as fundamental part of the construction of new cultures and civilisations is definitively outdated?