Imagining the city as a construct capable of growing upon and regenerating itself based on a cyclical model stretches back into the most ancient history, to the origins of the city itself. A practice that is once again central to our contemporary era when considered as part of sustainable strategies for planning and managing the built environment. The construction industry, as we know, produces the greatest damages to the environment in all of its phases: from the preparation of raw materials and components to the construction site to the use and operation of what is built. The projects selected for this issue present a vast range of situations in which the principles of recycling are applied not only to buildings, dilapidated areas or entire landscapes. They also demonstrate the ability to trigger virtuous processes of regeneration extended to the broader physical, social and economic context. Furthermore, this logic assigns the architect a determinant role in controlling the diverse phases. Designers are asked to guarantee a process that minimises energy demand, pollution, the use and waste of raw materials, opting for reuse and preparing a building for other possible future uses. This role is even more effective when supported by an holistic model and an integrated approach to design that coordinates supply chains, guiding results toward an efficient use of resources and reducing damages to the environment. The People’s Pavilion, a temporary service structure erected in the centre of Eindhoven, is emblematic; in addition to reutilising a notable quantity of plastic waste material, the Pavilion is the result of an innovative approach based on components and materials made of secondary raw materials. Used in this way they assume a greater value than that originally assigned them, demonstrating the concept of a circular approach to architectural design. Adapting instead of demolishing well-conserved existing buildings to host diverse functions and reactivating abandoned urban spaces to socially and economically revitalise neighbourhoods are now widespread practices in many European cities. These increasingly more common situations stimulate the creativity of architects and offer important occasions for bringing new and meaningful life to once obsolete buildings. A perfect example is offered by the transformation of an abandoned space beneath the Central Railway Station in Milan, once used to store goods and distribute the mail, into a Memorial to the Holocaust. The refurbishment strategy adopted by the architects proved successful in terms of both the overall quality of space and its symbolism.

Imagining the city as a construct capable of growing upon and regenerating itself based on a cyclical model stretches back into the most ancient history, to the origins of the city itself. A practice that is once again central to our contemporary era when considered as part of sustainable strategies for planning and managing the built environment. The construction industry, as we know, produces the greatest damages to the environment in all of its phases: from the preparation of raw materials and components to the construction site to the use and operation of what is built. The projects selected for this issue present a vast range of situations in which the principles of recycling are applied not only to buildings, dilapidated areas or entire landscapes. They also demonstrate the ability to trigger virtuous processes of regeneration extended to the broader physical, social and economic context. Furthermore, this logic assigns the architect a determinant role in controlling the diverse phases. Designers are asked to guarantee a process that minimises energy demand, pollution, the use and waste of raw materials, opting for reuse and preparing a building for other possible future uses. This role is even more effective when supported by an holistic model and an integrated approach to design that coordinates supply chains, guiding results toward an efficient use of resources and reducing damages to the environment. The People’s Pavilion, a temporary service structure erected in the centre of Eindhoven, is emblematic; in addition to reutilising a notable quantity of plastic waste material, the Pavilion is the result of an innovative approach based on components and materials made of secondary raw materials. Used in this way they assume a greater value than that originally assigned them, demonstrating the concept of a circular approach to architectural design. Adapting instead of demolishing well-conserved existing buildings to host diverse functions and reactivating abandoned urban spaces to socially and economically revitalise neighbourhoods are now widespread practices in many European cities. These increasingly more common situations stimulate the creativity of architects and offer important occasions for bringing new and meaningful life to once obsolete buildings. A perfect example is offered by the transformation of an abandoned space beneath the Central Railway Station in Milan, once used to store goods and distribute the mail, into a Memorial to the Holocaust. The refurbishment strategy adopted by the architects proved successful in terms of both the overall quality of space and its symbolism.

RECYCLING PRACTICES BETWEEN ECOLOGY AND REGENERATION – Pg. 4

Paola Guarini

RECYCLING LANDSCAPES: FROM WASTE TO RESOURCE – Pg. 12

Vincenzo Gioffrè

RECYCLING OR RECLAIMING? FROM THE ECOLOGICAL PARADIGM TO DESIGN EXPERIMENTS OF TRANSITION – Pag. 21

Consuelo Nava

An Artifact of Infrastructural Archaeology as a Place for the Polarisation of Memory

An Artifact of Infrastructural Archaeology as a Place for the Polarisation of Memory

Milan Central railway station, inaugurated in 1931, was designed to host an almost imperceptible network of service spaces beneath the public level, for loading/unloading and storing goods. The central portion of this level, designed to host new spaces for the postal service, with a 35,000 square metre area, was occupied by a platform with 24 parallel railway tracks, served by turntables; lifters also permitted the vertical movement of convoys from the upper tracks to the service tracks below and vice versa. This mechanized and abandoned belly of the station was transformed into a place of memory when RFI-Rete Ferroviaria Italiana granted the Milan Shoah Memorial Foundation Onlus with a portion of this space. As Morpurgo and de Curtis pointed out, “there exists a network of implicit connections that forever links this architecture-infrastructure with the geography of European deportations.” The functional machinery of the postal services area, invisible and extraneous to life in the city, was transformed between 1943 and 1945 into a device for deporting Jews and political opponents to the concentration camps.

Reuse and Enhancement of a Former Industrial Building

Reuse and Enhancement of a Former Industrial Building

This former eighteenth century paper mill, rebuilt in 1869 by Gustave Eiffel, is now home to the hub of a multinational leader in the production of innovative materials. The project develops around a large void a fluid and dynamic space. Environments designed specifically for particular uses alternate with large modular spaces, while circulation takes place in a continuous space fused with work and event spaces. The principal element of the Centre is located on the ground floor: a large internal square defined by a large stepping ramp connects the building’s two levels. On the second floor of the open space, covered by steel trusses and flooded by natural light, a series of balconies overlooking the lower level define flexible spaces for shared work, events and presentations. The project maintains the characteristic value of Eiffel’s structure, without affecting its reading, and also boasts a playful side: a slide for adults connects the building’s two levels, set parallel to the stepping ramp in the internal void.

Recovery of Former Railway Structures and Urban Regeneration in Spain

Recovery of Former Railway Structures and Urban Regeneration in Spain

Two renovation projects completed in Burgos and Valencia by Contell-Martínez Arquitectos share the intent to reutilise former railway buildings and both make recourse to the insertion of a limited number of elements with a strategic role and pared down language. The project in Burgos involved the renovation of the historical early twentieth century Railway Station and its transformation into a multipurpose recreational centre. The renovation project recovered the original qualities of the station by eliminating a mezzanine added during the twentieth century. The same logic of optimising new insertions and the successful contrast between new elements and historical masonry was adopted in the transformation, at the Parc Central di Valencia, of Pavilion 3 of the former railway complex into a multipurpose space for exhibitions and performances. Both projects contribute to the recovery of abandoned buildings, within a broader urban regeneration program, collaborating in the transformation of parts of the city, while pursuing the objective of maintaining the memory of the places and the charm of the ancient railway structures.

Original Spatial Qualities and Innovative Technologies in a Former Grain Silos

Original Spatial Qualities and Innovative Technologies in a Former Grain Silos

With the project for the Zeitz MOCAA Heatherwick Studio accepted and won the challenge presented by reimagining a monumental industrial structure constructed in the 1920s and decommissioned in 1990. The project literally carved the spaces required into the existing silos, creating unprecedented forms from a quasi-monolithic structure. The most suggestive intervention is that to carve out an atrium that replicates the form of a kernel of corn, scaled to 27 metres in height. It becomes the iconic formal matrix of the carving, made possible using digital technologies projected onto the silos and physically traced into the concrete walls. The spatial refurbishment triggered at the Grain Silo Complex appears fully aligned with other renewal projects in the harbour area of Cape Town. Made possible by innovative surveying and structural reinforcement technologies, the project is well integrated within a context of a cultural transformation that it has also come to symbolise.

Innovation in the Circular Project of a Multi-purpose Pavilion

Innovation in the Circular Project of a Multi-purpose Pavilion

Recognized as a milestone in circular design, the People Pavilion represents an avant-garde design experimentation for the new frontiers of architecture. Created on the occasion of Dutch Design Week 2017, the pavilion in its construction not only recovers a considerable amount of plastic waste, but no building material is irreversibly compromised during construction and no resources are taken to landfill after decommissioning. The pavilion wants to found “a new paradigm”, in its life time and subsequently in the narration of the processes it triggers, or rather in the need for a radical change in architectural thinking, which moves innovation towards a circular model in the management of resources but that is able, significantly, to eliminate the environmental impact of the construction industry, already in the design phase, with choices coming from a radical position.

Conservation and New Insertions in a Former Railway Shed

Conservation and New Insertions in a Former Railway Shed

The new Tilburg public library is the result of a daring adaptive reuse project for a former locomotive shed. The project is structured on the logic of conserving and preserving the atmospheres and spatial qualities of the original locomotive hall and establishes a synergic relationship between new insertions and existing elements testifying to the area’s industrial past. The intervention defines a system of planes on three different levels linked by stairs and stepped platforms; the spaces created fully conserve the perception of the wide roof and the original proportions of the hall. The complexity of the interiors is mutated by the presence of six very large fabric screens that slide in dedicated rails adjacent to the roof to create spaces for artistic performances, lectures or environments that require a greater degree of privacy than the public spaces of the library.

Reconversion of an Historic Building into a New Cultural Hub

Reconversion of an Historic Building into a New Cultural Hub

The intervention is a complex mix between new construction, refurbishment and the design of public space. The two new volumes are clad in a continuous surface made from multicoloured ceramic elements that appears to have been cut away in correspondence with the openings and entrances, revealing the structure in exposed concrete. The component of reuse is represented by the renovation of the former Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie. This sixteenth century building was restored to host high-end retail, restaurants and event spaces and trigger flows that establish relations with the museum district. The spaces at ground floor were imagined as a showcase open to the public. The cloister was covered by a new roof made of a steel structure and plastic tarps to facilitate the use of services and the possibility to host events. The M9 redesigns a fragment of the city and its new and restored buildings trace paths for the valorisation of its urban condition.

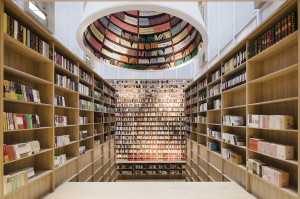

A place dedicated to Culture as Urban Catalyst in a Commercial Building

A place dedicated to Culture as Urban Catalyst in a Commercial Building

The design is inspired by the desire to improve the economic functions of an existing building and to enrich the city by introducing a new space dedicated to culture.The spatial result surely rewards the original decision to enrich the vertical circulation of the building, which already consented an uninterrupted view of the two public atriums, by new unexpected vistas. The new emphasised vertical tension is amplified not only by the non-stop movements of clients, but also by the large central oculus that catalyses these forces in a constant dynamic whose rising motion is a strong attractor for visitors. In addition to its successful design, the project also initiates an interesting reflection on the possibility to identify a compromise between the economic and financial requirements of private clients and public interests. It demonstrates an intelligent integration between spaces capable of becoming an extension of the city and of creating porous thresholds between interior and exterior.

A Revitalized Urban Space in an Old Soviet City

A Revitalized Urban Space in an Old Soviet City

The project for Azatlyk Square is part of a strategic plan that aims to improve living conditions in Russia’s cities and involves both public and private subjects. The new square thus begins with a space previously imagined and never realised. It is crossed by a large horizontal axis that, theoretically, was intended to connect the town hall with the Lenin Museum and become one of the city’s major attractions and spaces of leisure. The old axis, completely unrecognisable, was moved to the lower edge of the lot and the centre was organised as a series of “rooms” designed to host different functions and uses. The new centre of the site, now freed up, was transformed into an urban carpet: a succession of three public squares, with injections of colour provided by furnishings and plantings, liven up the greyness of the adjacent city, configuring flexible and multipurpose spaces.

The dismantling of a Shopping Mall as a Chance of Creating a New Public Space

The dismantling of a Shopping Mall as a Chance of Creating a New Public Space

Tainan Spring project recycles an old shopping mall built in 1983; this construction fell into disuse as online shopping expanded. As a result, city government decided to reconvert the site. The strategy adopted is an attempt to recover, through a reinterpretation, the underlying resource that characterised the site: the presence of water. In fact, from the seventeenth century, the Tainan water network was an important part of the development of maritime industry and fishing. The project is configured as a new landscape suspended between the memory of the past and the desire to offer a new urban habitat, in the form of an architectural space built according to the principles of a circular economy and able to extend the lifecycle of pre-existing elements and generate new values. The solid volume of the old building was inverted to create a void. The basement level became a protected urban space lowered, with respect to the street level to which it is connected by stairs.

ARGOMENTI

– L’ingegneria del Tevere a Roma: i muraglioni e il ponte alla Magliana – Pag. 114

– L’installazione temporanea “Radura della Memoria” nel futuro Parco del Polcevera a Genova – Pag. 120

LIBRI – Pag. 124

NOTIZIE – Pag. 126

Questo post è disponibile anche in: Italian